Victoria City Tour

Chinese Cemetery – Harling Point

The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association cemetery at Harling Point, known simply as the “Chinese Cemetery”, was started in 1903, when the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association purchased this land for a cemetery. It is located on Crescent Road.

The Chinese Cemetery is listed on the Canadian Register of Historic Places and is a National Historic Site of Canada.

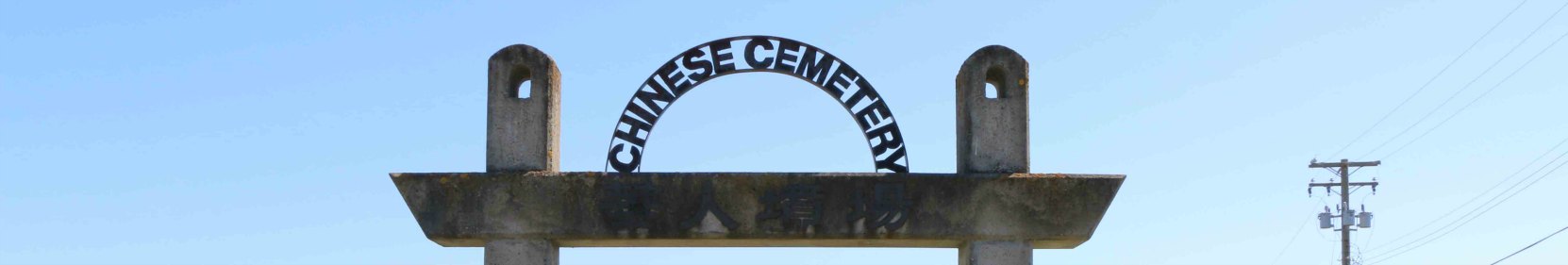

The entrance gate to the Chinese Cemetery. This gate is typically locked so go down the road to the left of the photo and you’ll find another gate near the waterfront.

Here is a map showing the location of the Chinese Cemetery at Harling Point:

Here is a Google Street View image of the entrance to the Chinese Cemetery at Harling Point:

Inside the Chinese cemetery, there is a large gray concrete structure with the two chimneys near the waterfront. This is an altar. Offerings of food and flowers for the deceased are left on the altar and incense is burned in fireplaces at the base of each chimney.

A Brief History of the Chinese Cemetery

The Chinese Cemetery is listed on the Canadian Register of Historic Places and is a National Historic Site of Canada.

Prior to 1903, Chinese burials had taken place in a low lying section of Ross Bay Cemetery which often flooded during heavy rains and storms. At that time, Ross Bay Cemetery was divided into different sections according to religion and/or ethnic origin.

Here are some historic photographs showing Chinese funerals at Ross Bay Cemetery:

- BC Archives photo D-05245 – Chinese funeral procession to Ross Bay Cemetery, circa 1890

- BC Archives photo D-05992 – Chinese funeral, circa 1892. Although the caption does not mention the specific location, it must be Ross Bay Cemetery.

- BC Archives photo A-02919 – Chinese funeral at Ross Bay Cemetery, circa 1895

- BC Archives photo A-02918 – Chinese funeral at Ross Bay Cemetery, circa 1895, with ceremonial offering of roast pig

- BC Archives photo D-05257 – Chinese funeral at Ross Bay Cemetery, circa 1900

- BC Archives photo D-05664 – Chinese funeral at Ross Bay Cemetery, circa 1900. Note the altar in this photo and its similarity to the altar in the Chinese Cemetery.

- City of Victoria Archives photo M00631 – circa 1898. photographer: Francis Rattenbury

- City of Victoria Archives photo M00632 – circa 1898. photographer: Francis Rattenbury

- City of Victoria Archives photo M00633 – circa 1898. photographer: Francis Rattenbury

The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association was dissatisfied with the section of Ross Bay Cemetery assigned for Chinese interments and purchased this land at Harling Point in 1903 as a cemetery specifically for the Chinese community.

This land at Harling Point was selected as a cemetery site because of it’s favourable “feng shui”, or harmony with nature . As a very basic [emphasis on “very basic”] explanation of what gives this cemetery “favourable feng shui,” the site is flanked by higher land on three sides and by water on the other. It’s also protected by the Azure Dragon, which is the hill on the east side of the cemetery, and the White Tiger, which is the lower elevation on the west side near Crescent Road. You’ll find a sign near the altar explaining the Azure Dragon and the White Tiger.

In addition, the water is considered a symbol of wealth and affluence; mountains are thought to give life. So the Straight of Juan de Fuca and the Olympic Mountains visible to the south contributed to the site’s feng shui.

There was also a Chinese belief that a dead person’s soul hovered above their grave and it was thought that the souls of those buried at Harling Point would enjoy watching ships pass by in the Straight of Juan de Fuca

This cemetery was not just for people from Victoria’s Chinese community. It was intended for Chinese from across Canada. At that time, there was a Chinese belief that if someone had been born in China but died outside China, their soul would be unable to rest until their remains were sent back to their home in China for burial.

Since Victoria was the most convenient Canadian port closest to China, Victoria’s Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association assumed responsibility for collecting and storing the remains of Chinese from across Canada as well as the responsibility of shipping those remains back to China for burial. Remains would be shipped to Victoria from across Canada and stored in a brick building, known locally as “the bone house”, in the Chinese Cemetery [note: the “bone house” is no longer standing.]

Because of the expense of shipping individual bodies to China, remains were stored here at the Chinese Cemetery until there were enough to justify a large shipment to China.

Every seven years the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association would arrange a single bulk shipment of remains to China. These shipments stopped when war broke out between China and Japan in 1937. After the Japanese surrender in August 1945, fighting in China between the Communists and the Nationalists still prevented shipments of remains from resuming.

When the Chinese Communist Party took power in China in 1949, it banned further shipments of remains to China.

But Canadian Chinese communities still shipped remains to Victoria for shipment to China and the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association continued to store those remains here.

By 1960, it appeared clear that the Chinese government would not change its policy of banning the shipment of remains to China so, in 1961, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association returned most of the stored remains to surviving relatives in Canada. But 820 sets of remains went unclaimed.

The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association separated these remains according to the deceased person’s home county in China, and, in 1961, buried them in 13 mass graves, most of which are between the waterfront and the gravel path near the altar.

The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association still owns this cemetery.

The Chinese Cemetery is listed on the Canadian Register of Historic Places and is a National Historic Site of Canada.

Here are some more links to historic photographs of the Chinese Cemetery:

- BC Archives photo G-04513 – This photo is identified as being at the “Chinese Cemetery” but it is dated circa 1895, meaning that it’s likely at Ross Bay Cemetery.

- BC Archives photo I-50512 – the altar in the Chinese Cemetery. This photo is dated “circa 1900” but it has to be 1903 or after 1903. This photo is interesting as it shows the brick work construction of the chimneys and two steps (no longer extant) leading up to the altar.

- BC Archives photo G-03076 – a memorial service at the altar of the Chinese Cemetery. The photo is dated “circa 1890” but it clearly shows the altar in this cemetery, so it has to have been taken in 1903 or after 1903

- BC Archives photo A-00982 – Chinese funeral procession at Yates Street and Blanshard Street, showing the Carnegie Library, circa 1910. The procession would likely have been heading here to the Chinese Cemetery.

- BC Archives photo D-01061 – the altar in the Chinese Cemetery, circa 1929

- BC Archives photo I-03368 – Chinese Cemetery, 1981

- BC Archives photo I-03366 – Chinese Cemetery, 1982

- BC Archives photo I-03367 – Chinese Cemetery, 1982

Some Other Interesting Features Of Harling Point

Wild Flowers & Plants

A number of endangered and threatened species of wildflowers grow in the Chinese Cemetery. One notable example is Macoun’s meadowfoam (Limnanthes macounii), which is one of the rarest plants in the world and was thought to be extinct until it was discovered growing in the Chinese Cemetery in 1965.

Geological Features

There are also some interesting geological features at Harling Point. One geological feature is glacial rocks deposited here about 12,000 years ago as the glaciers receded at the end of the last Ice Age; the other feature is a fault line between two ancient continents.

If you walk past the altar to the point where the gravel path is closest to the water, you’ll see two large rocks on the shoreline which are a different type of rock than the rock they are resting on. Both rocks were dropped here by glaciers as the ice sheets that covered Vancouver Island during the last Ice Age receded about 12,000 years ago. You’ll also see large gouges and grooves that were carved into the rock along the shoreline by the pressure of ice during the last Ice Age.

These two large rocks were deposited at Harling Point by glaciers as the ice receded at the end of the last Ice Age, 12,000 years ago.

One of two large rocks which were deposited at Harling Point by glaciers as the ice receded at the end of the last Ice Age, 12,000 years ago.

There is a Coast Salish legend about the larger of these two rocks left on Harling Point by the Ice Age glaciers. According to the Coast Salish legend, this rock was originally a seal hunter who was standing on the shore trying to harpoon seals in the kelp bed offshore. As he was hunting, the Salish god Qals paddled by in a canoe with his friends Raven and Mink. The canoe startled the seal hunter, who swore at Qals.

Qals quickly responded to the hunter’s insult by turning the seal hunter into stone.

One of two large rocks which were deposited at Harling Point by glaciers as the ice receded at the end of the last Ice Age, 12,000 years ago. A Coast Salish legend says this rock was once a seal hunter who insulted the god Qals, who responded by turning the hunter to stone.

One of two large rocks which were deposited at Harling Point by glaciers as the ice receded at the end of the last Ice Age, 12,000 years ago. A Coast Salish legend says this rock was once a seal hunter who insulted the god Qals, who responded by turning the hunter to stone.

The other significant geological feature at Harling Point is a fault line between two ancient continents.

If you look along the shoreline by the rocks you’ll see an ancient fault line between two ancient continents. On the seaward side of the fault line, the rock is a lighter colour than the darker basalt rock closer to land. 300 million years ago the ancient continent of Wrangellia formed as one of the earth’s crustal plates near where the equator is today. Over 260 million years, Wrangellia shifted to its present position, where it forms part of the coastal mountains of North America, including the Wrangell Mountains in Alaska, the Queen Charlotte Islands or Haida Gwai, Vancouver Island and parts of the southwestern coast of British Columbia.

The southern tip Wrangellia is now at Harling Point where it collided, 40 million years ago, with part of another ancient continent now referred to as the Leech River terrane.

The fault line where two ancient continents collided can be seen along the shoreline at Harling Point.

Would you like to leave a comment or question about anything on this page?

Error: Contact form not found.

Get Social